Contemplation: Markus Döbeli >< Indian Ritual Celebration

A Walk,

by Rainer Maria Rilke

My eyes already touch the sunny hill.

going far beyond the road I have begun,

So we are grasped by what we cannot grasp;

it has an inner light, even from a distance-

and changes us, even if we do not reach it,

into something else, which, hardly sensing it,

we already are; a gesture waves us on

answering our own wave…

but what we feel is the wind in our faces.

The first chapter of Vishnudharmottara, an ancient Indian treatise on art and aesthetics, emphasizes the abstract elements of art—its underlying formal structures and rhythms—rather than subject matter and iconography, reveals an important Indian belief about the highest purpose of art. Art’s purpose is not to depict stories portraying gods and their symbols, but to produce a state of mind ultimately leading to spiritual liberation. The purpose of the art object is to induce a particular state of consciousness. It does not represent or symbolize that state, but by various means, leads the viewer to it.

Contemplation, or dhyana in Sanskrit, has a long history and deep cultural significance in Indian culture, bringing about connections with the inner self, thereby achieving spiritual growth, mental and emotional balance, as well as inner peace.

Ritual sculptures serve as a focal point for contemplation and meditation in religious and spiritual practices. They aid in visualization and generate a feeling of connection to the deity or spirit they represent. A statue of Buddha, as an object of meditation, helps to cultivate feelings of peace, calm and enlightenment. Ritual sculptures are an important part of spiritual practice, facilitating connections with the divine, towards the achievement of a state of inner peace.

Abstract paintings can evoke a contemplative response of the beholder by encouraging them to engage with the work emotionally and intuitively. Facilitating a more open-ended interpretation it inspires the viewer to reflect in a more personal way. Abstraction opens itself to the viewer, who may project their own thoughts and feelings into the painting, a pathway to a deeper commitment through contemplative understanding. Within the compositional field, the eye finds itself drawn into the colors, textures and forms of the work, experiencing dhyana—absorption as the final step toward meditation.

Markus Döbeli’s paintings are hung up on the wall separately, one at a time. In his essay, written on the occasion of his exhibition at Döbeli Kunstmuseum Winterthur (2010), Dieter Schwarz writes that ‘’each painting seems to be painted for itself’’, and ‘’each painting is a stand-alone piece, which makes his work all the more remarkable. There is no consistent formal vocabulary, no particularly memorable stylistic gestus. What his paintings all share is the natural way in which they materialize. When you look at them on the wall, they are not immediately apparent. The longer you look, the more they begin to take shape; slowly the painting begins to emerge.’’

Placing Döbeli in the romantic history of painting, Schwarz is joined by Bice Curiger. In her text ‘’Eyes, my nostrils’’’, she cites Hegel’s notion of ‘’feeling soul’’. The deepest spiritual freedom, the sensuous expression (in color or words) of this inner sense of reconciliation constitutes what Hegel refers to as the ‘’beauty of inwardness’’, or ‘’spiritual beauty’’.

- Elaine J. Hitchcock Levy

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2016

- Acrylic on canvas

- 190 cm x 210 cm

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2017

- Acrylic on canvas

- 141 x 107 cm

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2017

- Acrylic on canvas

- 141 x 107 cm

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2022

- Watercolor on paper

- 58h x 76w cm

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2022

- Watercolor on paper

- 58h x 76w cm

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2022

- Watercolor on paper

- 58h x 76w cm

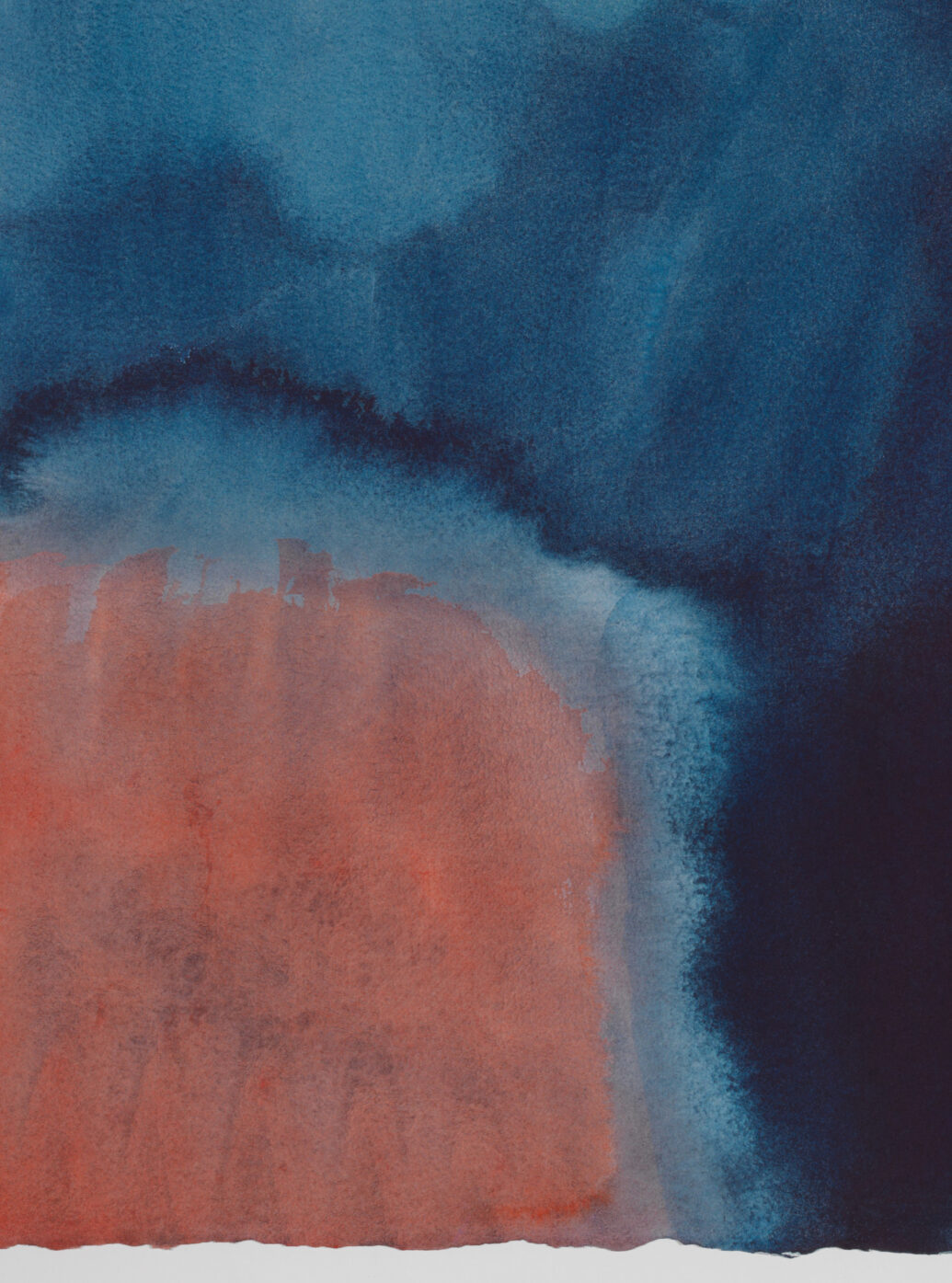

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2022

- Watercolor on paper

- 58h x 76w cm

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2017

- Watercolor on paper

- 55.50h x 75.50w cm

Markus Döbeli

- Untitled, 2022

- Watercolor on paper

- 58h x 76w cm

Unknown

- Shiva Lingam, 10th–12th century

- Vietnam, Champa

- Height: 70 cm - Width and depth: 24 cm

- Provenance: The Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica (The Ritman Library), Amsterdam

Unknown

- Stucco Head of Buddha Shakyamuni, circa 4th century

- Gandhara, present-day Pakistan

- Heigth: 21 cm - Width: 12.5 cm - Depth: 15 cm

Unknown

- Stone Lingam, Age unknown

- India

- Height: 29 cm

- Diameter: 16 cm

Unknown

- Head of Buddha Shakyamuni, circa 4th century

- Stucco Gandhara, present-day Pakistan

- Height: 52 cm (20 1⁄2 in)

- Provenance: Private collection Japan, 1970’s

Unknown

- Holy water containers, 18th century

- Bangladesh

- Various dimensions